Part 2: Jack Heistand, Chairman of the TBD

To help commemorate its 25th anniversary, the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) reached out to Blake J. Harris, the best-selling author of Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo, and the Battle That Defined a Generation and The History of the Future: Oculus, Facebook and the Revolution That Swept Virtual Reality to document the behind-the-scenes origins of the rating system for video games and how it has evolved over the past quarter century. Content Rated By: An Oral History of the ESRB provides eyewitness accounts from the key people involved in the ESRB’s creation and its development into one of the country’s finest examples of industry self-regulation.

PART 2: Jack Heistand, Chairman of the TBD

On January 6, 1994, over 75,000 folks from various areas of the consumer electronics business flocked to Las Vegas for the year’s Winter Consumer Electronics Show (CES). There, the Software Publishers Association (aka the “SPA”) gathered dozens of people from the video game industry to discuss the development of a unified rating system.

At this point in time, the SPA—which boasted over 1,000 member companies—was the nation’s pre-eminent trade association for software creators, manufacturers and distributors. Typically, the association was best known for its anti-piracy efforts (highlighted by their popular “Don’t Copy that Floppy” marketing campaign”); but with the recent pressure from Congress, the trade association had started to turn its attention towards ratings.

“Companies such as Sega, 3DO, Atari, Acclaim, id Software and Apogee already have and use rating systems,” explained Ken Wasch, who was the Founder and President of the SPA. “So there are rating systems in use today. But a proliferation of rating systems is confusing to retailers and to consumers alike.”

To solve this problem, Wasch believed that his organization was the answer. Together, with five other software-related associations, the SPA was in the midst of establishing a “Computer Game Ratings Working Party” so as to eventually create an independent rating board with the power to “penalize wrongdoers,” “keep pace with technological advances,” and “advertise the ratings so that they become as well known to purchasers as movie ratings are today.”

In concept, this generally made sense to Jack Heistand, SVP at Electronic Arts. But in execution, he had a different vision.

JACK HEISTAND (EA): I just thought it would be much more efficient to build our own system.

If there were any doubts as to why it might be important to build something from the ground up—something devoted specifically to the video game industry—all Heistand had to do was point to the event that he and his fellow executives were at.

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): Every year, twice a year actually (once in the summer, then again in the winter), we all went to the Consumer Electronics Show and showed off our latest products. But for some reason, they didn’t think highly of the video game industry. So they would put us in the back of the hall; or by the adult porn section; or one year, even, they actually had us in a tent. And it happened to be raining that year, and the tent leaked all over some of our Genesis displays.

JACK HEISTAND (EA): I remember that year—when they had us in that little tent. Meanwhile, they treated the TV guys and the car stereo guys like royalty.

DON JAMES (NINTENDO): There was a lot of bad blood. A lot of people felt like we were being treated as second-class citizens to the rest of the industries there.

With this in mind—and in order to avoid a similar fate of, say, feeling like second-class citizens to longer-tenured members of the SPA—Heistand approached EA CEO Larry Probst.

JACK HEISTAND (EA): I said, “Let’s get all the CEO’s together and we should form an industry association and I will chair it. Larry said, “That’s a great idea.” And within a couple hours we were able to set up a meeting with the heads of the biggest companies in the industry.

JACK HEISTAND (EA): EA, at the time, had no first-person shooters. The bulk of our revenue came from sports games. But we were motivated to get rid of the pall that the controversy [about violence] was putting over the entire industry. If we weren’t going to find a solution—if we weren’t going to “self-legislate,” if you will—then others were going to do it for us. And I also thought it was the right thing to do. I really believed in my heart that we needed to communicate to parents what the content was inside the games.

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): So we had this secret meeting in Vegas…

DON JAMES (NINTENDO): Where we decided that as an industry we should have a trade association. And it was kind of funny because Howard Lincoln and I were the two people who were in that discussion [from Nintendo] and at the end of that meeting, Howard looked at me and asked, “Can you handle these guys?”[laughing] I said, “Yeah, sure.” Then he said, “Don will represent Nintendo.”

DOUG LOWENSTEIN (ROBINSON LAKE SAWYER MILLER): At that point, I was only peripherally involved. I was working at a strategic communications firm and we were working a little bit with Electronic Arts, but not around any of the issues of violence and games. The consensus amongst the industry’s leadership was that the [Congressional] hearings had been pretty disastrous. And the industry needed to respond to what had increasingly been perceived as a real threat to the underlying business.

JACK HEISTAND (EA): I really became fond of Doug—thought he was just a buttoned-up guy. And he was really helpful as an “outsider” giving advice to those of us in the industry.

DOUG LOWENSTEIN (ROBINSON LAKE SAWYER MILLER): Like any new industry…well, it wasn’t new since games had been around for a while, but “new” in the sense that it was new as a cultural and political target. Most industries don’t prepare for that. They often become targets because they are new and different. The people who are involved in building these industries are not spending a lot of time worrying about the Federal Trade Commission or Congress…so, they’re never prepared for suddenly being in the cauldron of public policy controversy. In that sense, I think, the people in the industry who were involved were trying to feel their way along. This was new territory to them. At the same time, there was certainly a “wild west” aspect to the industry in the sense that there were some who dug in and said, “Screw ‘em! We’re going to make the games we want and they can’t touch us!” But the cooler heads recognized that there was a real existential threat to the industry, a real threat of government regulation, and just giving critics the finger and hoping they’d go away wasn’t prudent or viable.

ARTHUR POBER (CARU): They had me flown down to Las Vegas and all of these software developers were sitting around a table screaming and carrying on with each other. And at a certain point I just stood up and said, “Guys, I gotta tell you: if you can’t be unified here, behind closed doors, you certainly can’t walk outside when the press is gonna be there.”

As the game industry attempted to organize itself, Senator Lieberman upped the ante and on February 3, 1994, he introduced the “Video Game Rating Act of 1994,” which called for the establishment of something called the “Interactive Entertainment Rating Commission.” As per Senator Lieberman’s bill, this Rating Commission would consist of five members—each selected by the President of the United States—and given the mandate to establish standards capable of sufficiently warning “parents and users of the violence or sex content of video games.”

Meanwhile, throughout early ’94, folks from the game industry continued trying try to come up with some semblance of a plan that could work for everyone. Early in the process, they received some encouraging news—that Walmart, the nation’s biggest retailer, had agreed to only stock games that were rated. But other than that, especially as far as the rating system itself, it was tough sledding at the outset. However, time was of the essence—especially after Congress called for another set of hearings in March.

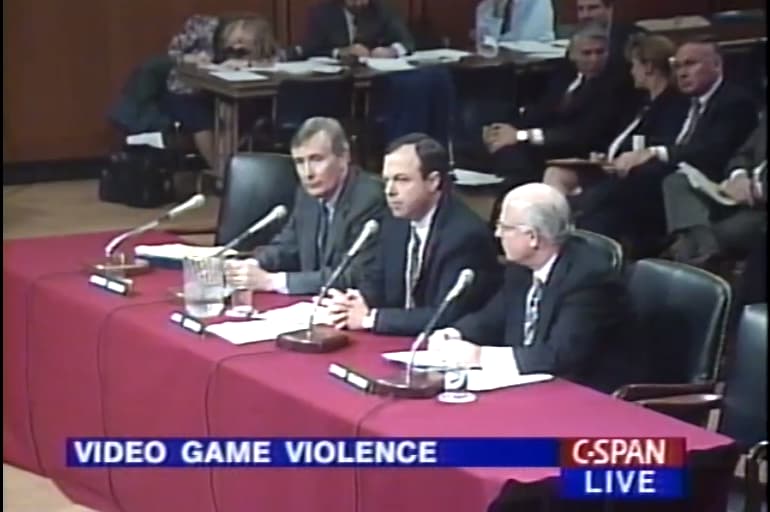

On March 4, 1994, Senators Lieberman and Kohl welcomed back representatives from Sega and Nintendo to further discuss the issue of violence and video games. This time, however—instead of watching the proceedings unfold on CSPAN—Jack Heistand would be there, on hand to personally explain what steps the game industry was taking to address legislators’ concerns.

“I’m here on behalf of our industry rating system committee…” Heistand explained. “Besides EA, committee members include Acclaim, Atari, Nintendo, Phillips, Sega and the 3DO Company. Together, these companies comprise over 60% of the interactive market. And…we strongly believe that it’s time to put the game controls in the hands of parents and adult consumers through the creation of a universal, responsible, reliable, understandable and independent rating system.”

Heistand then briefly outlined some of the unique challenges facing the game industry—namely that whatever solution the game industry came up with would need to satisfy an incredibly diverse group of publishers, spanning from “garage operations” to “multi-national companies”; and that the number of games to be rated would likely surpass 2,500 titles each year.”

“To put this into perspective,” Heistand continued, “that’s four times the level that the Motion Picture Association of America reviews annually…With this context let’s get to the meat.”

Heistand then listed thirteen points that his just-under-two-month-old coalition had agreed upon:

In response, Senator Lieberman called this “a very encouraging report.” Both he and Senator Kohl were particularly encouraged by the news that Walmart had already agreed to stock only rated products. “I think you’re doing great,” Senator Kohl added. “It’s a wonderful start.”

And, of course, that’s all it really was: a start. In order to keep the government off their backs, Jack Heistand and everyone else in his yet-to-be-named trade association (and their yet-to-be-formed ratings board) would need to actually deliver on all these things and more.

…

Read Part 3: Parallel Tracks >>

The next six parts of Content Rated By: An Oral History of the ESRB include the development of the ratings and enforcement system, how ratings are assigned, garnering support from video game retailers and how the ESRB created a scalable global rating solution to meet the needs of mobile app and other digital game storefronts. Read Part 3 in the ESRB About section.

Blake J. Harris is the best-selling author of Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo and the Battle that Defined a Generation, which is currently being adapted for television by Legendary Entertainment.