Prologue and Part 1: Doom to the Power of Ten

To help commemorate its 25th anniversary, the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) reached out to Blake J. Harris, the bestselling author of Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo, and the Battle That Defined a Generation and The History of the Future: Oculus, Facebook and the Revolution That Swept Virtual Reality to document the behind-the-scenes origins of the rating system for video games and how it has evolved over the past quarter century. CONTENT RATED BY: An Oral History of the ESRB, provides eye-witness accounts from the key people involved in the ESRB’s creation and its development into one of the country’s finest examples of industry self-regulation.

Prologue

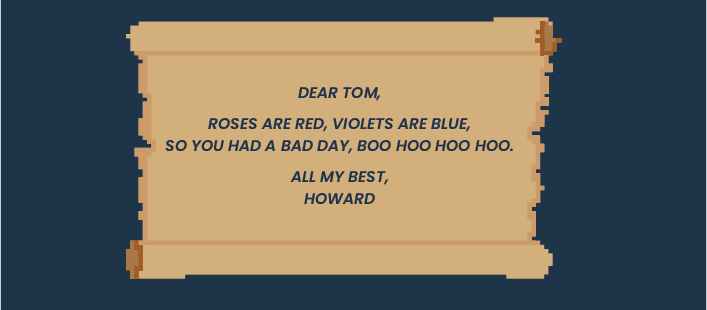

On April 2, 1994, Howard Lincoln—who, just months earlier, had been made the Chairman of Nintendo of America—published a poem in a press release aimed at his chief competitor, Tom Kalinske, the President of Sega of America:

Reading these words, Tom Kalinske was not amused. But truth be told—at this critical moment in time—poetic barbs were the least of Kalinske’s worries.

Cut to: One Year Earlier

ARTHUR POBER (CARU): Back in 1993, I was the Director of the Children’s Advertising Review Unit [aka CARU, part of the Better Business Bureau and the self-regulatory arm of the children’s advertising industry]. And at CARU, both Sega and Nintendo sat on my boards. So, you know, over time I got to develop a pretty strong relationship with Tom Kalinske and Howard Lincoln. And because I also had a strong relationship with the FCC and other folks in Washington, I kept hearing whispers that the government was taking a closer look at the video game industry. So, every few months, I would basically say to Tom and Howard, “Look, your industry is under scrutiny right now. They’re going to go after you guys; so, if you’re looking to avoid censorship, you better get organized—you better come up with a rating system” [laughs]. But did they listen to me? And their answer to me was basically, “Yeah, yeah, yeah. We’re never going to band together because it’s a competitive and very adversarial marketplace.”

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): It was extremely competitive. We had the Genesis—our 16-bit system that we thought was way better than their SNES—and we were giving Nintendo a run for their money. Just two years earlier, Nintendo controlled over 90% of the market and by this point—after the release of Sonic 2—we had just about pulled even with them.

ARTHUR POBER (CARU): Eventually, Tom Kalinske calls me and says, “You know, I think you’re right about a rating system. It’s the right thing to do. So, Sega is going to take the leadership on this. Would you like to be a part of this group?” Absolutely! I told Tom that this sounded great and that I was glad he was being so responsible about it. Then I called up Howard and Howard was very adamant that Nintendo was not going to be part of any group that was created by Sega [laughs]. Which, you know, may sound a little petty, but you could understand where he was coming from. Because—again—the industry was extremely competitive: everyone was at each other’s throats. It was like Doom… only to the 10th power, at that point.

Of all the games to come out in 1993, Doom—the beloved, bloody, first-person shooter developed by id Software—was arguably the most violent. But, at least initially, Doom was only available on PCs, so it wasn’t exactly a pressing concern for Sega or Nintendo. But what very much was on their respective radars (and what each company hoped would be one of their biggest games of the year) was the year’s hottest arcade game: Mortal Kombat.

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): So we had actually come up with our own rating system at Sega.

To rate games appearing on their hardware, Sega had created something called the “Videogame Rating Council” (VRC) in June 1993. The VRC would review upcoming games and give them one of the following three ratings:

- GA: General Audiences (Appropriate for all audiences)

- MA-13: Mature Audiences (Parental Discretion Advised

- MA-17: Mature Audiences (Not appropriate for minors)

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): For our Sega rating system, we hired independent educators, psychologists, child development experts and sociologists; and [this Council] was run by Dr. Arthur Prober, a noted educator in New York City.

Arthur Pober was a longtime educator who—in addition to his work for CARU—was, at this time, best known for being the former Principal of Hunter College Elementary School; Director of Special Programs for the Board of Education for the City of New York; and Director of Gifted and Talented Education for New York City, among others. Pober had a doctorate in Educational Psychology and Organizational Development, which he had received from Yeshiva University.

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): We tried to get the Motion Picture Association of America on board, but Jack Valenti [president of the MPAA] wouldn’t agree to lend his system to us and so we had to develop our own. But I think it was a really good first step and we immediately started rating all our games so that it was very clear to the consumer which were for children and which were for adults.

RILEY RUSSELL (SEGA): We used “G.” There was “MA.” I’m not sure what else we used, but it was a lot like the MPAA. Gail Markels, who ultimately became the lawyer for ESA, was at MPAA. She called me and threatened me that they were going to sue us for the use of the marks. I was a young lawyer—probably more cocky than I should have been—and I said, “You can’t trademark a ‘G’.”

GAIL MARKELS (MPAA): As head of state government affairs at MPAA, we saw an explosion of bills attempting to regulate video game content with no one stepping up to oppose the bills. This was a huge concern because if efforts to ban or regulate video games were successful, movies could be next. The MPAA stepped up to kill the bills to protect our member’s interests.

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): Once we had our rating system in place, we felt we would be safe. And with Mortal Kombat coming (as well as a couple of more mature titles on Sega CD), we felt that we were doing the responsible thing. So we were feeling confident. And then we started feeling even more confident after we learned about what Nintendo had asked Acclaim to do.

Acclaim was the publisher who would be putting out Mortal Kombat. And they would be doing so on both Sega and Nintendo on September 13, 1993, in a much-hyped release event they had dubbed “Mortal Monday.” And on that fateful day, consumers would discover that there was one glaring difference between the Sega version and the Nintendo version of Mortal Kombat.

HOWARD LINCOLN (NINTENDO): Mr. Arakawa [Nintendo of America’s President at the time] and I were well aware of the Mortal Kombat coin-op game and we knew it was a very violent game with a lot of blood. We had some pretty strict standards, and we had been making sure that both Nintendo first-party and third-party games adhered to those standards…in part because we were selling games to kids and we just didn’t like the violence. So we had long discussions at Nintendo about whether we should allow the blood in and I ultimately decided that we would not. And I told them [Acclaim] that we have to take it out and, I think, we changed it to green blood.

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): The Nintendo version showed green gore. Well, what human being has green gore in ‘em? We released Mortal Kombat in its original form—in other words: you can see the blood in it—but we also clearly rated the game. We made it clear that this game was for “Mature” audiences. And as a result, we stayed true to our audience of teenagers, college kids and young adults. At that time, forty percent of our players were over the age of eighteen so clearly we needed to provide games for the over-eighteen audience. And I thought reaching that audience was incredibly important—not just for our business at Sega, but because I felt that if the industry was ever going to be considered more than just a child’s toy, we had to have games appealing to teens and adults.

DONA FRASER (ACCLAIM): The game industry was changing; it was getting older.

In the early 90s, Dona Fraser served as the Advertising Manager for Acclaim Entertainment.

DONA FRASER (ACCLAIM): The first game I ever worked on was Mortal Kombat. And, yeah, sure, we were aware of what people were saying about the game. But the counterargument we used to make amongst ourselves—as staff— was that we all grew up watching Bugs Bunny and the Road Runner and we’re fine [laughing]! Nevertheless, we ended up changing the color of the blood to green for certain territories. Like in Germany we couldn’t show red blood. And then, of course, there was Nintendo…

HOWARD LINCOLN (NINTENDO): We got our clocks cleaned! We absolutely got wacked on that.

TOM KALINSKE (SEGA): I think we outsold the Nintendo version five-to-one.

DON JAMES (NINTENDO): Nobody bought our game! They all bought Sega’s game because everybody wanted red blood. That was sort of a big learning experience for us.

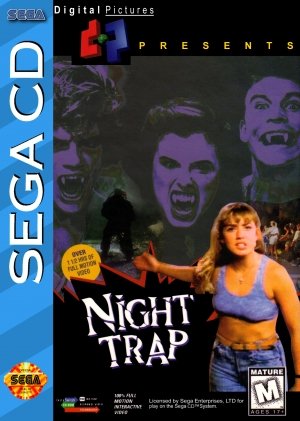

Meanwhile, as Sega racked up huge sales with Mortal Kombat, additional concerns about the content in video games began to swirl around a pair of much less popular games: Night Trap and Sewer Shark, both of which were exclusively available on Sega’s CD-based platform.

HOWARD LINCOLN (NINTENDO): Sega introduced Night Trap and the instant I saw what that game was about I knew we were going to be in front of Congress. It was obvious. I remember telling [Nintendo of America’s VP of Marketing and Communications] Perrin Kaplan, “Mark my words, this game will cause such a reaction by parents, by the media, it’s going to get to Congress and there will be a hearing.”

On October 20, 1993—mere weeks after the release of Mortal Kombat—California’s Attorney General, Dan Lungren, spoke to a group of police investigators at an event in Los Angeles:

“We’ve got impressionable young people dealing with interactive games that are very realistic and I wonder if that is what we should be teaching our kids. The message is: destroy your opponent. I would ask you if that is very different from some of the messages in gang culture.”

The following month, Lungren upped the ante asking game manufacturers to stop selling games that teach youngsters to “demean and destroy.”

“Continual exposure to violent images and themes in various entertainment may not be the direct cause of these atrocious acts,” Lungren said in a letter to a dozen of the game industry’s most prominent companies. “[These types of games] have a deadening, desensitizing impact on young, impressionable minds.”

GAIL MARKELS (MPAA): Before the MPAA, I was a prosecutor. As a former Assistant District Attorney in Brooklyn NY, I knew that factors such as poverty, demographics, dysfunctional families and drugs impacted the crime rate and that movies, music or video games were not factors. Facts matter. As video games became more popular, the crime rate plummeted.

Regardless, Attorney General Lungren continued to raise awareness over what he believed to be a significant issue. Soon enough, his concerns were being echoed by a handful of politicians. Most prominently: Senator Joseph Lieberman, who—on November 17, 1993—distributed the following letter to his colleagues:

Dear Colleague:

A woman is stalked in her home, mutilated and murdered. A man is instructed to “finish” his opponent in a martial arts contest and chooses to rip his opponents still beating heart out of her body. These examples may sound like shocking cases stemming from the current epidemic of violence plaguing the United States. In fact, they are witnessed by children every day. Worse, children participate, since these examples are drawn from some of the most popular and most disturbing of a new generation of video games.

Gone are the days when video games were just Pac-Man and other quaint characters. Advances in technology permit the latest video games to use real actors and actresses to depict murder, mutilation and disfigurement in an extremely graphic manner. And the technology is rapidly becoming ever more realistic. Today’s graphic games may seem mild compared to the CD-ROM and virtual reality systems, which will change the market very soon. These games will come right into our living rooms if a pilot cable channel for video games slated to begin next January proves successful. At a time when real violence is threatening to tear the fabric of our country, these games glorify the most depraved acts of cruelty. While parents across the country are trying to teach their children to abhor violence, these games encourage children to enjoy violence. The Washington Post recently quoted a 14-year-old boy on the appeal of one particularly disturbing video game: “It’s violent. It’s real. You can freeze the guy, cut him up, shoot him with a hook that has a rope so you can pull him. I like the moves and stuff.”

The video game industry has not addressed the danger presented by their latest creations. In fact, some have made violence a selling point. One game was introduced to great fanfare on “Mortal Monday.” Currently, parents have a very difficult time knowing which video games are slightly violent and which are truly repugnant. No uniform system exists for warning a concerned parent about the violent content of a video game, which she is buying for her child.

I plan to introduce legislation and hold a hearing on this topic…

In the meantime, hoping to squelch this issue before things got worse, Tom Kalinske sent the following letter to Nintendo’s Minoru Arakawa:

Dear Mr. Arakawa:

Though we have never had the occasion to meet, I believe recent developments merit this attempt to open a dialogue with you.

As you know, our companies embrace different approaches to handling fighting games and adult-appropriate interactive entertainment. I think the time has come for a comprehensive industry-wide approach to the issue of informing consumers about our products so they can make intelligent purchase decisions. In short, I think it is necessary for our nascent industry to grapple with, and for you and I to proactively lead, that industry to a uniform, responsible solution to this issue, one of which we all can be proud.

As the leading companies in the video game category of the larger interactive media and entertainment industry, you and I can forge a bond of personal commitment to doing what is right for all involved—ensuring free choice and enabling people to control what comes into their own homes.

I am urging you in the strongest possible way, and with the greatest respect, to join us at Sega—and the scores of independent software companies who make software for both Nintendo’s and Sega’s hardware platforms—in adopting the Sega rating system administered by the independent Videogame Rating Council (VRC) which is composed of highly respected PhD’s from a variety of disciplines, or to adopt some other similar rating systems and to communicate it on your new products.

You know, as do I, that your company creates and/or permits marketing of software titles for your game systems that portray a level of violence as great as anything in the industry. In fact, the PhD’s of education, childhood development, psychology, and sociology on our own VRC tell us any game where the objective is to demolish enemies through martial arts or weapons should be designated for an audience over thirteen years of age (no matter if animated blood is included or not). Nintendo’s game development guidelines are an inadequate way: 1) to insure consumer’s freedom of choice, 2) to enable consumers to gain enough information that would allow them to exert control over the types of software titles brought into their homes, and 3) to guarantee they are always appropriate for the age of the user in that home.

I know you must appreciate that your guidelines were probably appropriate for this business when it was less sophisticated, and when over three-quarters of the user base was under 17 years old—in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Now, when our technology is so much more sophisticated, and increasingly attractive to adult audiences, it seems to me an industry- wide rating system is the type of responsible self-regulation you and your company should join us in adopting.

I am sure that we could find sponsors in our government’s legislative branch who would assist us in getting an anti-trust exemption to collaborate on this matter if that is a concern that is inhibiting your positive response to this entreaty.

Mr. Arakawa, I ask you to please, with an open mind, consider this suggestion and to consider the benefit we all gain by doing the right thing for the consumers—adults and children—who have been so generous in rewarding both our companies with such great success during the last decade…

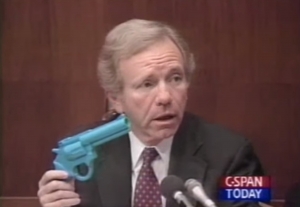

Given that many at Nintendo felt Sega had “created this entire problem” and was “now dragging us into their mess,” Kalinske’s letter proved to be a non-starter. And so, on December 9, 1993, representatives from Sega and Nintendo traveled to Washington, D.C. to testify before the Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, and the Subcommittee on Regulation and Government Information of the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs.

Speaking on Nintendo’s behalf, Howard Lincoln explained that Nintendo didn’t produce violent games—they had even censored Mortal Kombat, after all, losing a lot of money in the process! Meanwhile, Bill White (speaking on behalf of Sega) conceded that, yes, Sega did produce games for a more mature audience than Nintendo, but they did so responsibly—pioneering an entire rating system and marking their products appropriately.

JACK HEISTAND (EA): I remember watching this all play out on C-SPAN: representatives from Nintendo and Sega testifying in a Judiciary Subcommittee chaired by [Senator] Joseph Lieberman. And what was taking place was not good. It was basically just an hour-long, back-and-forth, finger-pointing session over which company’s games were worse. Like I said: not good. And I don’t just mean for Nintendo and Sega, I mean for all of us. This had the potential to be incredibly harmful to everyone in the industry.

One week after the first Senate hearing, Toys ‘R’ Us—one of the nation’s top retailers—announced that they would stop selling games that they viewed as “too violent for children.” For now, only one game (Night Trap) would be banned. But behind-closed-doors, at the upper levels of the most prominent game companies, there was a chilling sense that this was just the tip of the iceberg. And, if so, then was there anything that could possibly be done to get back on track?

JACK HEISTAND (EA): Well, I had an idea…

…

Read Part 2: Jack Heistand, Chairman of the TBD >>

The next seven parts of CONTENT RATED BY: An Oral History of the ESRB include the development of the ratings and enforcement system, how ratings are assigned, garnering support from video game retailers and how the ESRB created a scalable global rating solution to meet the needs of mobile app and other digital game storefronts. Read Part 2 in the ESRB About section.

Blake J. Harris is the best-selling author of Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo and the Battle that Defined a Generation, which is currently being adapted for television by Legendary Entertainment.